First generation immigrants from Japan to Canada, known as Issei, began to arrive in 1884, and in the early 1900s they began to settle in the Fraser Valley, buying land in primarily Mission, Clayburn, and Peardonville.[1] Initially, the new landowners were single men who had come to Canada to work in mines, along the railroad, in the lumber industry, fishing, or on cargo ships, and following their decision to settle in Canada more permanently, they often traveled back to Japan temporarily to marry, or chose a picture bride.[2] Upon her family’s approval, the bride-to-be would sail to British Columbia to be picked up by her husband-to-be in Victoria or Vancouver.[3]

The men’s early encounters with the white community “occurred in the highly charged arena of competition for jobs” and almost always involved being placed in a segregated work gang and being paid lower wages.[4] In 1902, to discourage immigration, the BC Legislature “stripped the right of citizenship of immigrants from Asiatic countries” thus denying them the vote.[5]

Beginning a farm provided at least some agency and distance from such inequalities and allowed the new families “to construct their communities in the tradition of the Japanese farming village.”[6] By 1930, there were 103 Japanese-owned properties in Mission averaging 9.51 acres each, and since farming was also the most promising means of making a living and raising a family in the area, many of the new couples turned to berry farming, for which the area was and is well known.[7] Other ways that they could create and retain agency economically, politically, and socially “could be as simple as partaking in public education or as complex as winning the vote for Japanese Canadian First World War veterans, which occurred in 1931.” [8]

In 1938, a book titled, The Japanese Canadians, was written to attempt an analysis of historical and contemporary Japanese Canadian experiences in Canada, and while regrettably written from non-Japanese Canadian perspectives, it offers insight into the collective hostility shown politically, economically, and socially in British Columbia towards multiple generations of Canadians of Japanese descent. The book notes that the Japanese immigrants in the first thirty-plus years of the 20th Century were “blamed for loyalty to the land of their birth” and seen as an “economic threat.”[9] As will be made evident, however, this was thankfully not the perspective of all of their neighbours. The paradox of racism lies in that while the Japanese communities were seen as unwilling to assimilate because of their Japanese Language Schools, close-knit communities, cultural traditions, and religious celebrations, they were also disparaged when they made full use of public education opportunities for their children, the Nisei (second generation), and sought to mingle with the greater community.[10] For example, “after the Anti-Japanese Land Law passed the California Legislature in 1924, anti-Japanese enmity also increased in BC. Segregated education of Nisei children and other troublesome incidents became topics of ever day conversation.”[11]

Closer to home, these views presented themselves in not allowing Nisei children “living in scattered farming villages along the Fraser River…to participate in any prominent roles during annual events held by the public schools.”[12] On May Days, Nisei girls were never included in the list of potential May Day Queens and Maids of Honour. William T. Hashizume, a descendent of a founding member of the Mission Japanese Canadian community translated the recollections of Haney resident Yasutaro Yamaga who says that “at this, we felt outright indignation.”[13]

According to Yamaga, however, rural areas like the Fraser Valley were less prone to racial discrimination than urban centres and the coast, given that the families in smaller communities were more likely to come in contact with each other, including the children at school.[14] While this is only one perspective and contradicts a general understanding of the correlation between racism and rural communities (especially given the May Day example and other such discriminatory incidences), the realities of racism certainly became only more of an obstacle as the Nisei finished school. Whether or not the Issei sent their children back to Japan for their education, once graduated, many of the Nisei faced discrimination in the Canadian workforce like their parents, and this was only exacerbated by the fear induced by the war, especially following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941.[15]

Before reaching the events of the 1940s, however, it should be noted that “between 1922 and 1932, enrolment of Japanese in the provincial schools jumped from 1,422 pupils to 4,702, an increase of 230 per cent, or over ten times the increase of all groups in the Province for the same period.”[16] In Mission, the Nisei accounted for 3% of the Mission school population in 1918 and 30% by 1928.[17]

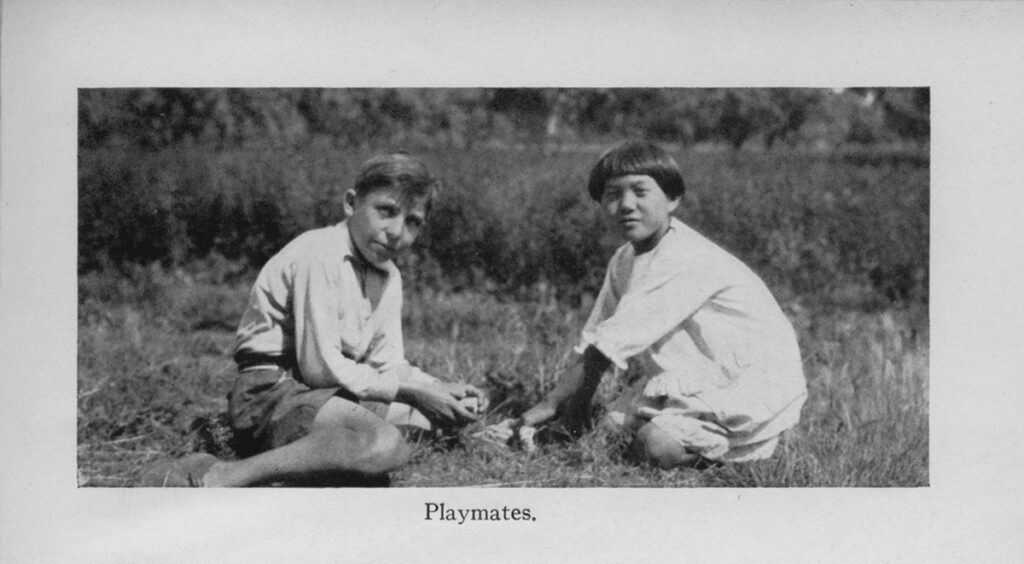

The dramatic rise in enrolment can be seen as a natural result of a new Japanese Canadian generation coming of school age, given that many of the immigrants began families soon after buying land, but it also “indicates wholesale participation in the educational life of the Province” which is supported by firsthand accounts.[18] Interestingly, the authors of The Japanese Canadians indicates that schools were a place free of prejudice which ideally would be the case, making it a true learning ground where differences would enrich the lives of the students and teachers alike.[19] While a broad and unsupported statement, the authors recognized that unlike the racist and unequal treatment the Issei had experienced, the Nisei had the opportunity to bridge two worlds, especially while in school and while playing and learning with the neighbour kids, without considering differences to the same extent or being subjected to the same prejudices.

One anonymous Japanese Canadian student recollects:

My childhood I passed as a Canadian, impervious to the external forces that would have made me otherwise. Public school, in which the greater part of my hours were spent, accomplished its objective, more or less thoroughly to make me a normal Canadian child. . . Death came painfully in the last years of my high school life. The Canadian within me slowly became extinguished. Persistently, the fact that I was of Japanese origin was imposed upon me. Rather unsympathetic teachers, prejudiced, often thoughtless students treated me as a different being, because of my physical characteristics, which I, in spite of every effort, could never hope to alter. [20]

While the phrase “normal Canadian child” shows the weight of an ingrained acceptance of racist sensibilities, it is true that although the Nisei were born Canadians, educated, and often experienced workers, having grown up helping on the farm or in family business, many of the second generation found “themselves almost as much the objects of discrimination as their fathers before them” once they entered the workforce.[21]

[1] “Rites of Passage Exhibit”, May 9-30, 1992. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[2] William T. Hashizume. Japanese Community in Mission: A Brief History 1904-1942 (North York: Musson Copy Centre, 2002), 4. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[3] Hashizume, 4.

[4] Anne Dore. “Transnational Communities: Japanese Canadians of the Fraser Valley, 1904-1942”, BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly, no. 134 (2002): 42.

[5] Yasutaro Yamaga. History of Haney Nokai, trans. William T. Hashizume (North York: Musson Copy Centre, 2006), 49. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[6] Dore, 43.

[7] “Rites of Passage Exhibit”; Hashizume, 4.

[8] Dore, 37.

[9] Charles H. Young, Helen R. Reid, and W. A. Carrothers. The Japanese Canadians (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1938), 132; Dore, 36. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[10] Young et al., 132.

[11] Yamaga, 50.

[12] Yamaga, 50.

[13] Yamaga, 50.

[14] Dore, 160.

[15] Dore, 62.

[16] Young et al., 132.

[17] “Rites of Passage Exhibit.” Mission Community Archives.

[18] Young et al., 133; 139.

[19] Young et al., 139.

[20] qtd. in Young et al., 140-141.

[21] Young et al., 145.