The Reach.

“Common”, “normal”, or elementary schools with possibly “upper” classes offered were, until the late 19th Century, the only general education available aside from university in Canada. High schools as we know them today did not exist.[1] Even when the need for further education in British Columbia was acknowledged in 1874 and high schools were slowly established, they were seen as optional means of advancing one’s education for specific careers such as teaching or commercial and technical studies and required entrance exams.[2] Even in the 1920-40s when the system had gained more structure and attendance statistics had increased dramatically province-wide, it was still not uncommon for children, especially those with a farming family or a family business, to finish after elementary school. The fact that Japanese Canadian youth attended consistently in the years leading up to 1942 speaks to how they valued education.

The Abbotsford, Sumas, and Matsqui News often highlighted the only high school’s events and milestones, as well as teachers and students’ promotions, including many Japanese Canadian youth. On August 27, 1930, an article ran, “Sumas-Abbotsford high school opens to its first pupils on Tuesday of next week . . . Eighty pupils, it is estimated will constitute the initial enrollment with the opening of the fall term. . . The new building with furnishings, will approximate a value of $20,000. . . Books required for the first year are: literature: The Golden Treasury of Canadian Verse (Stephen); Composition Through Reading (introductory course); history: World’s Progress (Canadian edition, West); Studies in Citizenship (McCraig); History of Canada for High School (McArthur); health: Human Physiology (Ritchie); French: Seipmann, Part I.”[3]

In 1936, Sumas-Abbotsford School was renamed in Philip Sheffield’s memory as the former district’s director of education.[4] The school’s “endeavour” was “to provide a curriculum and facilities of practical value to the boy and girl to better enable them to meet their economic and social problems. To this end we aim to make rural areas more attractive.”[5]

PSHS Grade 10 boys, 1939.

The Reach P13233.

PSHS Grade 11 girls, 1939.

The Reach P13234

The yearbooks shine light on the social, academic, and athletic atmosphere of the various classes. For example, Kimi Noda and Yoshia Sugimura were a part of the first Philip Sheffield graduation class in 1938.[6] Also, each student, whatever their grade, was forever commemorated for their talents or idiosyncrasies in simple rhymes. For example, in the 1938-1939 year, Sumi Kozai is described with the verses:

She stares and stares,

just watch her wonder grow.

At all the things

That she’s supposed to know.[7]

In 1939-1940 three Japanese Canadian students were in Grade 10.

Mary Oye was described as:

Our Mary is a clever miss;

Troubles and cares she can dismiss.

In Maths she’s tops (she’s always right),

Does well in sports, despite her height.[8]

There are no photographs of Mary Oye but below is one of Yoshia Sasaki who also participated in athletics.

Back row, second from left: Yoshia Sasaki.

The Reach P11594.

Sumi Noda was defined with the lines:

Lo and behold our composition king,

He’ll write on any subject or anything.[9]

Finally, Kuni Kozai was:

A clever lad is Kuni Kosai,

he even drives his car to school.[10]

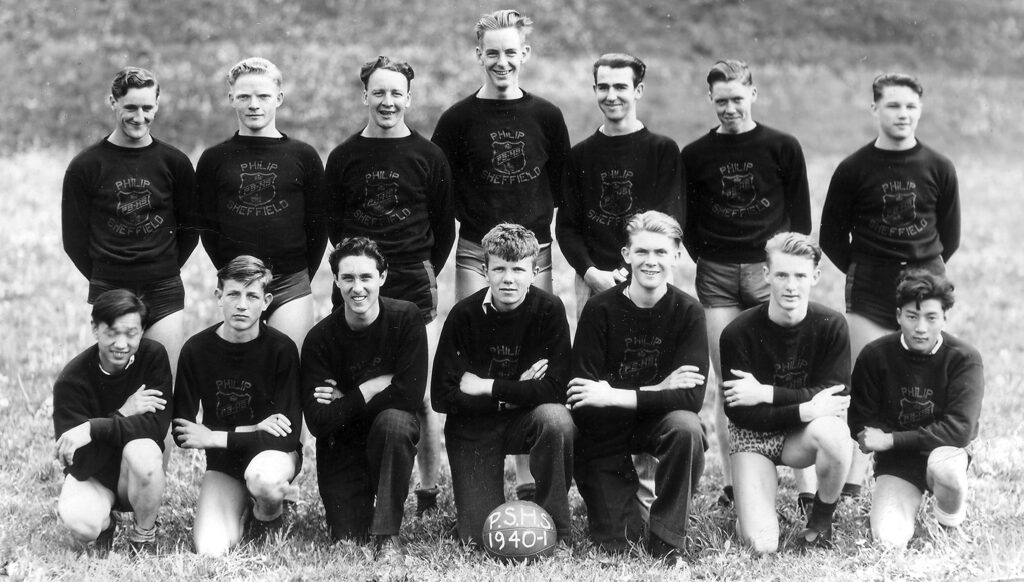

Pictures of the sports teams were also included,

Front, far left: Jiro Sasaki. Front, far right: Kuso Matsui.

The Reach P11595.

and the newspapers followed suit and highlighted the high school’s sports, including a field day in the July 7, 1937 edition of the Abbotsford, Sumas, and Matsqui News. Miyoshi Nakashima came in 2nd for the 75 yd. dash and 1st for the broad jump in the “Girls Under 14” category.[11]

With the beginning of the war came a change in curriculum with emphasis placed on raising money for the war effort and industrial training. How this affected or was experienced by the Japanese Canadian students in the Fraser Valley is unclear, but before Canada declared war on Japan in December 1941, there was already “industrial war training in Philip Sheffield High School” which was intended to “gives skill in aircraft production needs.”[12] The idea was to learn “to become vital parts of the Empire’s war machine. . . through the co-operation of the Department of Education and the Boeing Aircraft Company to meet an emergency caused by the shortage of men skilled in aircraft production work.”[13] The draw to the classes was that they “guaranteed positions in this industry” following graduation, as well as general skills in reading blueprints, working with industrial tools, and working with metal.[14] For all students, whether or not they participated in this class, the war was a consuming topic in their curriculum.

Following the removal of Japanese Canadian families from the area in 1942, Nisei children disappear from class photos.

[1] F. Henry Johnson. A History of Public Education in British Columbia (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1964), 57.

[2] Johnson, 58; 64-65.

[3] “$20,000 High School Opens on Tuesday.” Abbotsford, Sumas & Matsqui News (Abbotsford Archives, Abbotsford, BC), Aug 27, 1930.

[4] Sarah Evans and Aron Newman. A History of Philip Sheffield High School (from Prof. Robin Anderson, University of the Fraser Valley), 1.

[5] Abbotsford, Sumas & Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), Dec 23, 1936.

[6] Philip Sheffield High School. Consamannum 1937-1938. The Reach, Abbotsford, BC.

[7] Philip Sheffield High School. Consamannum 1938-1939. The Reach, Abbotsford, BC.

[8] Philip Sheffield High School. Consamannum 1939-1940. The Reach, Abbotsford, BC.

[9] Consamannum 1939-1940.

[10] Consamannum 1939-1940.

[11] Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (Abbotsford Archives, Abbotsford, BC),July 7, 1937.

[12] “Industrial War Training in Philip Sheffield High School Gives Skill in Aircraft Production Needs.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui (Abbotsford Archives, Abbotsford, BC), April 30, 1941.

[13] “Industrial War Training in Philip Sheffield High School Gives Skill in Aircraft Production Needs.”

[14] “Industrial War Training in Philip Sheffield High School Gives Skill in Aircraft Production Needs.”