Abbotsford Archives/P9320.

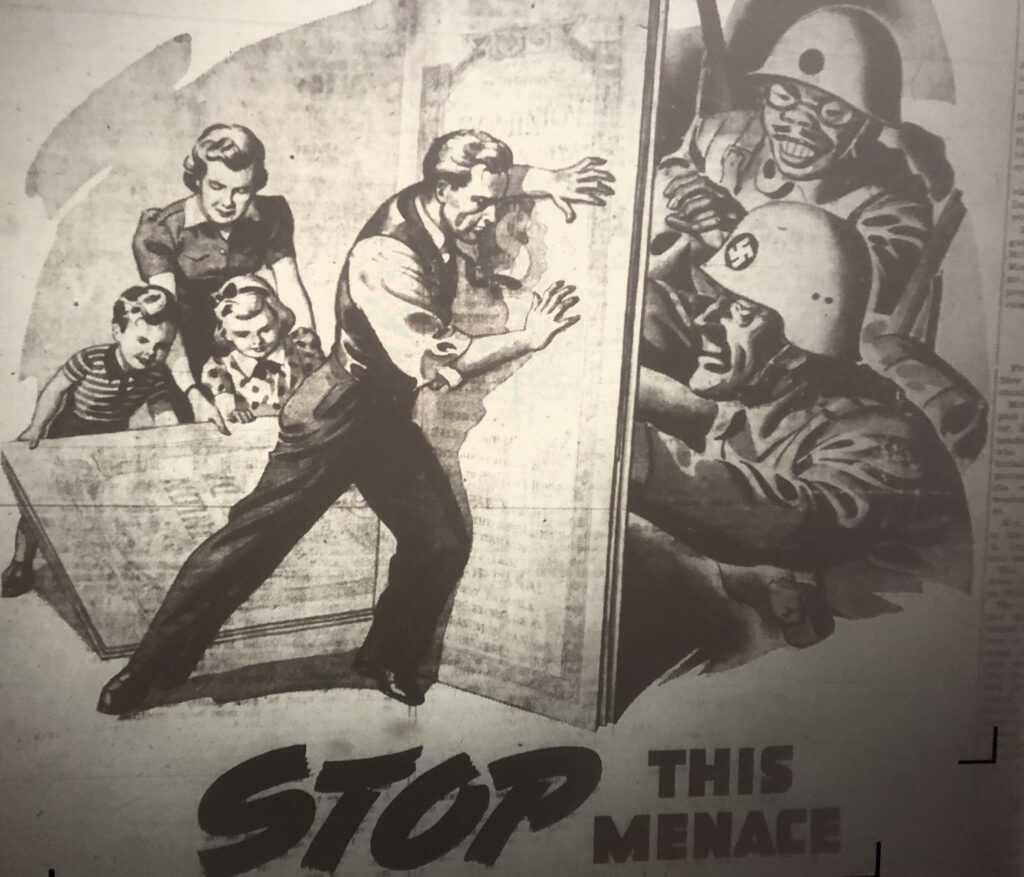

With World War II declared in 1939 and most significantly, the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, life changed drastically and tragically for Japanese Canadians even though the fighting took place far away from Canada and the Fraser Valley. What Hashizume describes as an “anti-Japanese movement” or magnified racism became impossible to ignore.[1]

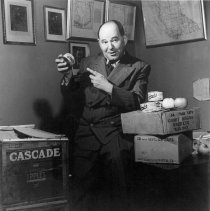

In an article with a racially degrading title “Would Ban Jap Trucks Until Berry Season”, George Cruickshank, M. P. for the Fraser Valley from 1940-1949 stated: “In view of the shortage of tires and likely of trucks, why not ban the use, between fruit seasons at least, of trucks operated by Japanese as well as their fish-boats?”

The Reach P11771.

He also urged curfew and declared that he had “wired Ottawa immediately on the outbreak of hostilities with Japan, following the treacherous attack on the USA” in order to establish a 5 pm to 8 am curfew.[2] On the same front-page of the newspaper, it reads: “Council Urges Mass Meeting on Jap Topic: Urges Associated Trade Boards to Sponsor Assembly”.[3] Council refers to the Sumas Municipal Council held mainly to address “public opinion regarding the 26,000 Japanese nationals and native born Japanese who are concentrated largely in the Valley.”[4] Again, in that same newspaper an article reads: “Propose Ban on Land Sales to Japanese” in which it recounts that the “Members of Matsqui Municipal Council” endorsed the ban “presented ‘on behalf of White farmers’” and to “protect their farming interests.”[5] The article notes the direct wording of the Assembly’s legislation on the matter, and gives further racialized descriptions by declaring that “no amount of naturalizing will ever make a Japanese anything but a Japanese.”[6] The bans were sanctioned, and they go on to justify their actions by stating that if the Japanese people had been “more evenly distributed throughout the Dominion”, had “inter-married”, and “learned our language more quickly” then “their racial characteristics might have been submerged or coalesced with the Canadian way of life. They have too readily adopted our Western economic way of life but they have preferred to retain their own old social habits.”[7]

All of their hateful statements and the newspaper’s presentation of them, reveal an ignorance concerning the Japanese Canadian communities, especially as those in power failed to factor in the diligent and positive participation of Nisei students in the public elementary and high schools both in curricular and extracurricular activities which included learning English and about Anglo-culture. There are also articles such as the one titled “Japanese Contribute to Red Cross” in the Fraser Valley Record on January 22, 1942, which specifies that $15 were donated by the Japanese Canadian Citizens League and $106.25 by the Mission Japanese Community.[8] This was after the attack on Pearl Harbour.

Certainly, the fear of the war’s outcome was real and justified in Canada, especially as the war stretched into a third year and the Pacific became a new front, but such fear also gave way to destructive panic, especially as the media and government worked off of already established prejudices. For example, another headline reads: “Fear Japanese”, saying that the “Langley Municipal Council is of the opinion that the Japanese in the district are as effectively organized as those in Hawaii at the time of the Pearl Harbour raid.”[9] Only a week later on January 21, 1942, the paper announced that, “Farm and fruit lands owned or operated by Japanese in what is known as British Columbia defense areas will come under the jurisdiction of a royal commission to be appointed by Ottawa in a few days.”[10] It also details that the Japanese “will be removed to inland points”, whether they are “national”, “naturalized-Canadians”, or “Canadian-born Japanese.”[11]

Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News, January 21, 1942. Abbotsford Archives.

George Cruickshank M.P, in his own words, took “a leading part” in convincing the federal government in Ottawa, along with other BC Members, that the removal of the Japanese necessitated urgent action.[12] He referred to the Japanese as “enemy aliens…irrespective of where they were born” and called that an “evacuation” of them be “completed by April 15th.”[13] Cruickshank spoke before the House of Commons: “We people of British Columbia are not asking; we are demanding where these Japanese are going to be removed to. I am not blaming Ontario or any other province for not wanting them, but I am warning this government that it will never put those Japanese back in British Columbia.”[14]

His use of “we” is a rhetorical “we” but despite the antagonism displayed in the newspapers and the federal government’s choice to act on such recommendations, neighbours such as Mr. and Mrs. Barnett, and the children who played and learned with their Japanese Canadian friends show that such words and actions did not represent the entire sentiment of British Columbia as Cruickshank believed, or at least presented for effect.

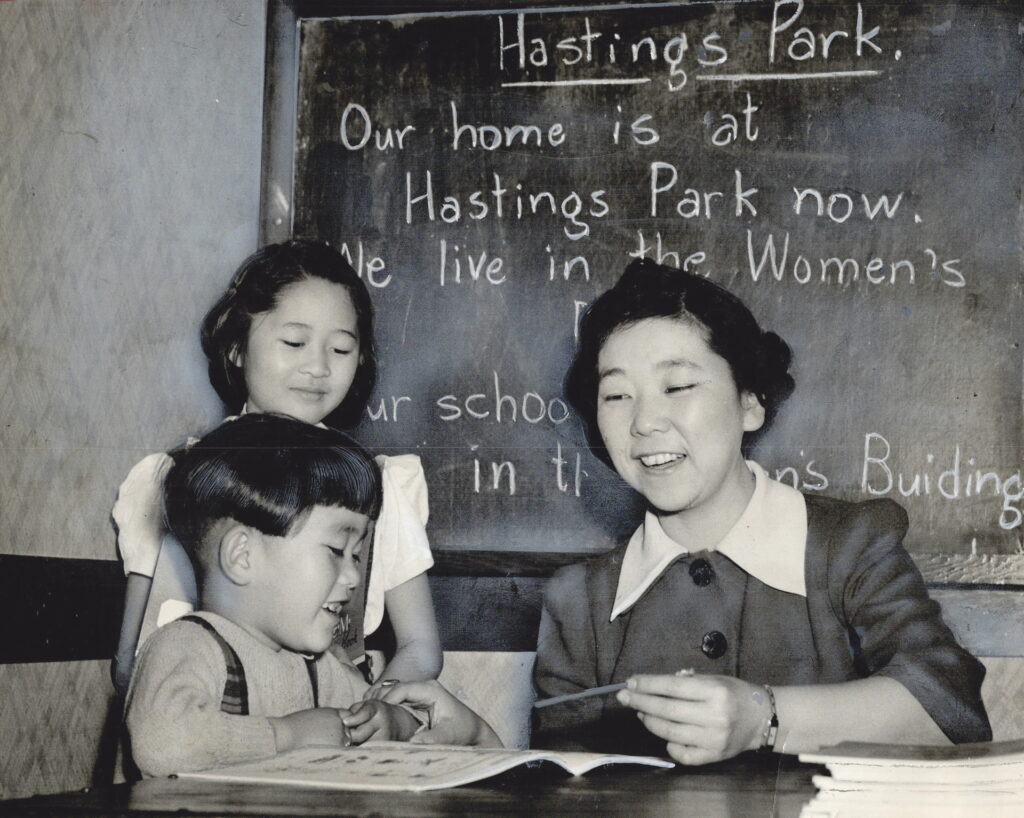

(courtesy Library and Archives Canada/C-057250). https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/hide-hyodo-shimizu

Around 100 Japanese families were living in Mission at the time of the displacement.[15] Homes, businesses, and assets were confiscated with the false promise of safe keeping. Approximately 1,274.381 acres and 273 lots were seized in the area, and this included the crops, Buddhist Society, Japanese United Church, and Japanese Farmer’s Association properties where the halls and subsequently Japanese Language Schools were located.[16] Hashizume consistently calls it an “evacuation” which was the term used in the period, but such a word gives the sense of providing protection for the evacuees when this was furthest from the reality they endured.

Tomiko Lillian Imakire attended Japanese Language School in Mission from 1927-28 with Mr. and Mrs. Kudo as teachers. Her family had come to Mission in 1920 to work, and after logging for some time, her father began a General Store where the whole family worked.[17] In May 1942, they were displaced and relocated to Raymond, Alberta where Tomiko describes the conditions as “Water – terrible, housing – poor.”[18]

(National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada/C-024452) https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment-of-japanese-canadians

Tomiko was one of the only Japanese Canadians to return to Mission following the end of the war and their later release. For her, Mission was home and she wished her children, the Sinsei, or third generation, to go to school there.[19]

The camps were haphazard, and apart from shelters, officials provided nothing in terms of supplies, clothing, food, or schooling. Nonetheless, schools were established in various settlements with the help of nearby churches or from others who took charge within the camps, often without any prior experience in teaching.[20]

Hide Hyodo Shimizu attended elementary and high school, and also studied at the University of British Columbia for one year before receiving her teachers’ certificate from Vancouver Normal School in 1926. Apart from being an activist for the right for the Japanese Canadian vote, she saw the need upon arriving at an internment camp for education to continue and began organizing a school. The British Columbia Securities Commission noticed her work and allowed her to develop a school system, including setting up teacher training for Nisei, ordering and distributing school supplies, and advocating for better treatment and facilities.[21] Although the displacement makes firsthand accounts of Fraser Valley Japanese Canadian students in the camps or on the beet farms scarce, if existent at all, the public records of Shimizu and the subsequent work of others who stepped up to the teaching challenge in unfriendly environments far from home, provides a window into the lives of a resilient and beautiful people.

[1] Yasutaro Yamaga. History of Haney Nokai, trans. William T. Hashizume (North York: Musson Copy Centre, 2006), 49. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[2] “Would Ban Jap Trucks Until Berry Season.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), January 7, 1942.

[3] “Council Urges Mass Meeting on Jap Topic: Urges Associated Trade Boards to Sponsor Assembly” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), January 7, 1942.

[4] “Council Urges Mass Meeting on Jap Topic: Urges Associated Trade Boards to Sponsor Assembly.”

[5] “Propose Ban on Land Sales to Japanese.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), January 7, 1942.

[6] “Propose Ban on Land Sales to Japanese.”

[7] “Propose Ban on Land Sales to Japanese.”

[8] “Japanese Contribute to Red Cross.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), January 22, 1942.

[9] “Fear Japanese.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), January 14, 1942.

[10] “Jap Farms to be Controlled by Commissions.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), Jan 21, 1942.

[11] “Jap Farms to be Controlled by Commissions.”

[12] “Geo. Cruikshank Describes Efforts of BC Members to Convince Ottawa on Necessity of Ousting Japanese.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), March 11, 1942.

[13] “Geo. Cruikshank Describes Efforts of BC Members to Convince Ottawa on Necessity of Ousting Japanese.”

[14] “Urges all Jap Farms be Taken Over by Custodian and Action to Save Crops; Would Extend Freight Rebate.” Abbotsford, Sumas and Matsqui News (The Reach, Abbotsford, BC), April 1, 1942.

[15] William T. Hashizume. Japanese Community in Mission: A Brief History 1904-1942 (North York: Musson Copy Centre, 2002), 1. Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[16] Mission Community Archives, Mission, BC.

[17] Tomiko Lillian Imakire. Rites of Passage Exhibit: Family History Survey, Mar 18, 1992 (Mission Community Archives, Mission. BC), 7.

[18] Imakire, 7.

[19] Imakire, 11.

[20] Greg Robinson. “Internment of Japanese Canadians.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, September 17, 2020. https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment-of-japanese-canadians.

[21] Emily Gwiazda. “Hide Hyodo Shimizu.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 15, 2019. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/hide-hyodo-shimizu.